RED

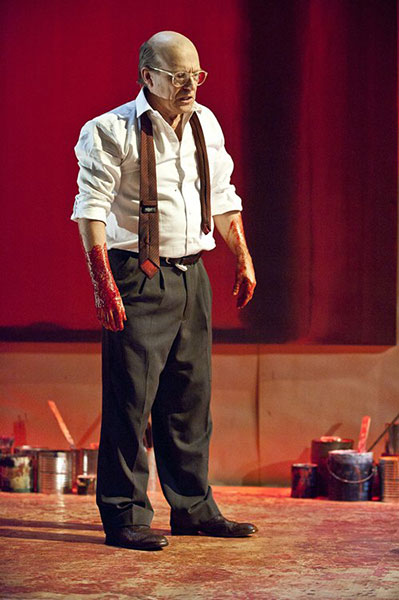

Michael Hurst's portrayal of Mark Rothko is a wonderfully nuanced study of complexity and contradiction.

Rothko's luminous rectangles of pure colour represent a final stab at the modernist project of creating an art that would usurp the function of religion.

As with earlier attempts to cram transcendence into the painted surfaces of abstract art, the promised epiphany never happens. But John Logan's Tony Award- winning play delivers a powerful testament to the heroism of Rothko's relentless devotion to an impossible task.

What makes the play so compelling is that Rothko is not put on a pedestal but neither is he subject to a clever postmodern deconstruction and the appealing mythology of abstract expressionism is accorded the respect it deserves.

Michael Hurst's portrayal of the legend is a wonderfully nuanced study of complexity and contradiction. For all his pomposity, arrogance and self-importance, Rothko emerges as a man driven by a fierce commitment to his art and a profound reverence for the traditions he was overthrowing.

Rothko's lecturing provides a comprehensive introduction to his metaphysical brand of expressionism.

Heady expositions on Nietzche's call for a dynamic equilibrium between Dionysian and Apollonian impulses are interspersed with intensely physical demonstrations of the business of painting.

Oliver Driver's unobtrusive direction combines well with John Parker's lovingly detailed recreation of the purposeful chaos of an artist studio and Brad Gledhill's lighting design subtly evokes the pulsing luminosity of Rothko's paintings.

But the play really comes to life in the artist's explosive confrontation with a younger painter who has taken on the thankless task of working as the sorcerer's apprentice.

Playing Rothko's assistant, Elliot Christensen-Yule carries off a remarkable transformation as he throws off his timidity and launches a formidable challenge to the master. The younger man poignantly reminds Rothko that his grandiose musings about the essential tragedy of human experience has left him without any understanding of the basic requirements of human decency.

The play is cleverly set at the moment when triumphant ascendancy of abstract expressionism is being undermined by the emergence of Pop Art.

The dialogue makes it clear that we are still coming to terms with implications of this watershed that saw the moral seriousness of high modernism replaced by the flippant, anything-goes irony of post-modernism.