Radiating Excellence

John Parker interviewed by Jim Barr and Mary Barr in John Parker CERAMICS

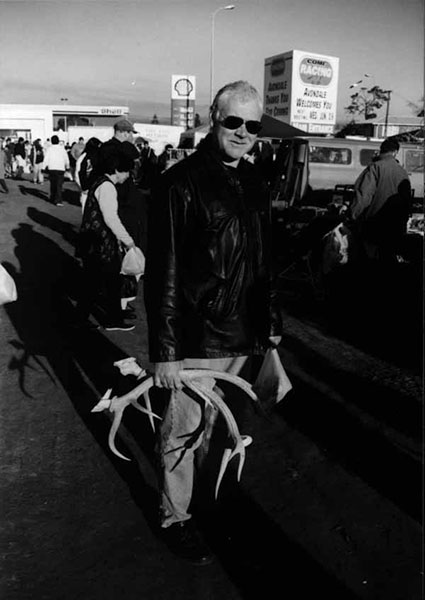

Jim's photograph from the Avondale flea market 1999

Knowing John all these years. Easy to remember some things; finding John at his wheel—so focussed but immediately engaged when he looked up; untold dinners and lunches; more schlock movies than is good for anyone. Over the years we have talked to John for hundreds—maybe thousands—of hours. But, when offered the chance to sit down and interview him, how little we actually knew. Of course we knew he was driven by passion, curiosity and an endearing inability to say no to anything. We suspected that he would feed our interest in how biography can trigger new and provocative takes on work. What we didn’t know, was how much we didn’t know! This interview is restricted to John’s ceramic life. Design, exhibition design, film criticism, professional magic, travel have been reluctantly excised.

The interviews on which this article is based took place over November and December 2001. They were then shaped and rewritten to make us all sound better than we were on the day.

When did you make your first ceramic?

It’s a roundabout story. I was very unhappy at university in the mid-60s. Unhappy because I told by the school careers adviser that I wanted to be an architect or an interior decorator. Her reply, ‘No, there are too many architects, and men are not interior decorators, do science.’ So I went to university to do maths, chemistry and physics. Because I’d wasted so much time in my last year at high school with the drama club, my parents said ‘No clubs.’ I was allowed to do one night school class, so I went with Ross Skiffington to Tamaki College and did pottery.

I’ve always made things. I used to make puppets and puppet theatres, magic tricks and in my playhouse I had a museum. Being an only child I think I’ve always done things with my hands. It was just something that I could do. My parents encouraged me. They’ve always encouraged my passions.

Getting back to the question, the first thing I made was a little kind of a coil thing. I remember cutting it with a knife and pushing it through so it was like a point—it was so silly. The whole process was interesting for me though. I was strong in the arms and I was really good on the wheel, quickly. I could control things. I found I could say that I wanted to make something of a certain shape and that would be pretty much the shape it would turn out.

The 60s were an important time for ceramics in New Zealand.

There was a huge craft revival movement. Margaret Milne, who was my teacher, had a kiln in her backyard. Ross and I used to go and help her mix clay, and hang around. I remember the first time we mixed clay. Afterwards Margaret gave us tea in pottery mugs, and I remember thinking, ‘These people really do it.’

If any one thing made a difference at that time what would it have been?

I think the big, big turning point for me was when I got my first car in 1967. It was a Mini. A friend and I drove down to the Coromandel and camped out on the hills. This was about two or three months after I’d started at Night School. I rang up Barry Brickell and said, ‘You don’t know me, but can I come and have a look at your kiln?’ Barry of course said, ‘Come on!’ And this green little boy who’d been to Night School classes with some ladies, suddenly came across this incredible life-style. Michael Illingworth was there making fibreglass figures. It was just amazing. When I got home I wrote to Barry and asked if I could work with him. He wrote back that he’d been sick and was getting behind on his work. If I wanted to come and help mix clay for an exhibition then I could come and stay. So I went. And I stayed for the varsity break.

What did you do at Barry’s, who did you meet and what did you all talk about?

Sam Pillsbury was there. And he and I foot-wedged clay together. And for this Barry paid me money! We all drank a lot of rough red wine. Barry was terribly affectionate to other people. People like Graeme Storm. Barry perpetuated the myth of Graeme making pots in a white boiler suit and never getting dirty. But Barry was outrageous.

A lot of people would put you more in the Graeme Storm category.

Well, there are times when I am. There are times when I’m glazing and I’m meticulously clean.

What else do you remember about the Brickell trip?

The Tchaikovsky violin concerto, which Barry played all the time and which I’d never heard before. Lots of people came and visited. May Smith the painter. Sam had gone camping with someone to paint and run out of materials, so they did all these drawings with coffee. For somebody who’d always lived at home with their parents it was pretty wild.

Did you have any idea then of making things for yourself?

No, I think I was still experimenting. I still believed people who used electric kilns were little old earthenware ladies who couldn’t do anything else. You had to be a real mud and water man. Dig the clay yourself; grind it with your teeth. It was partly the times and partly because we had such a reaction to the bone china that you had in your china cabinet at home. Crown Lynn, which one worships now, was part of what you were reacting against.

When I came back from my two weeks with Barry, Grant Hudson, who was interested in becoming a potter, and I built our first kiln at my parents’ house.

Who else were you in contact with at this stage?

Graeme Storm was very good to me. Pat Perrin was incredible. Grant and I were trying to do natural draft kilns in the height of suburbia. Huge smuts, all sorts of toxic muck going into the air.

One day after an all night abortive firing attempt Margaret rang Pat Perrin, and Pat said ‘Oh, tell them to come round.’ So Grant and I went. We were filthy, covered in diesel and there, in the middle of suburban Ellerslie, there was this huge bamboo forest. It was like going back in time. This large decaying villa where Phyllis, Pat and Yvonne had their studios. It was incredible. We used to always go there on Friday nights and sit in front of roaring fires. I heard my first Wagner there.

So how did you all know what to do?

Well you have to remember that in the late 60s and early 70s there was really only one book available. The Potter’s Book by Bernard Leach. Any glaze that anyone used came out of that. Later Daniel Rhodes’ Clay and Glazes for the Potter and Stoneware and Porcelain arrived with a new material dolomite in it. No-one had used dolomite before, so suddenly we had all these dolomite things. Then a little later came Carlton Ball’s Making Pottery Without a Wheel that introduced lower firing materials like gerstley borate. By then I’d started trying to use white earthenware clay, which was always available. But you couldn’t throw it, because of its non-plasticity. You could mold it, cast it, whatever, but you couldn’t throw it. So eventually people started mixing their own porcelain.

My history, which is very much the history of ceramics in New Zealand, is a history of technical advances. Getting high temperature electric kilns, discovering new materials, suppliers making new materials available.

And on the aesthetic side?

I’ve never drawn well. I’ve never painted. So I’ve decorated by banding lines. It’s always been simple. I suppose I’ve spent my life simplifying. I’ve always liked straight lines and finer things, and control. In my own work. And it was just so feasible. Nobody could make enough stuff. It was easy to sell work. Anything that was hand-made, no matter how bad, that was its virtue. If there was a crack in it, it was terribly Japanese. I used to think that all the Japanese stuff was a bit of a con-trick. Zen and the Art of one hand clapping and all that. I didn’t subscribe to it.

So what would you work have looked like at that stage in the early seventies?

It would have been cream and brown—but I thought of it as black and white! I had my first show in Hamilton in 1969, with Grant Hudson. I was trying to be minimal, but I was always being constrained by the random nature of the kiln and the impurities in the clay. Before I went to London, the most successful things I did were matte black and cobalt blue. Mavis Robinson gave me her little electric kiln and I did some low fire cadmium selenium reds with the unthinkable, a commercial glaze.

What was it about making ceramics that appealed to you?

It was something I could do. It’s hard to explain. Because I spend so much time by myself, I suppose I’m interested in making things hard for myself. I’m always setting rules. Then I see what can I do within them. Trying to make the neck on a bottle that’s slightly longer, slightly thinner. It takes my breath away. And I’ve always been fascinated by the technical challenges of it. I love the material in every facet of the process. I even like mixing all the dry stuff with water and sieving it! I just love every stage of it and especially setting up an exhibition, having an opening.

You’ve mentioned Trevor Bayliss as an important figure at this early stage.

Yes, he was at the Auckland Museum. He was another incredible mentor. He gave me the use of some cases at the museum and I did a Lucie Rie and Hans Coper exhibition, borrowing work from various people. It was around 1969 and Tony Birks’s book The Art of the Modern Potter had come out. That was the first time I really got the blast of Lucie Rie’s work. Len Castle had some and Barry had a little pourer. The first one I ever touched, was the one down at Barry’s. When I first saw it I knew I wanted to make to make things just like that.

What was it about Lucie Rie’s work that appealed to you?

I always liked the laboratory flasks and other equipment like evaporating basins in my chemistry set. And refinement appeals to me. In craft pottery books they would have industrial sections, with people throwing blanks and putting them on lathes and turning them. That certainly appealed to me. Lathe turning the big electrical insulators. I’ve always turned. I’ve never settled for the shape that ended up with my throwing, I’ve always modified them. It’s been the shape and the forms that have interested me.

But with Lucie’s work. Well, for a start, they were as fine as egg-shell. They were extraordinarily fine. The forms were Scandinavian modern and had nothing to do with Oriental shapes. They were light. They seemed to have a high degree of control and skill. To me she was someone who got what she wanted rather than settled for how they ended up. At the same time, her things are very organic when you see them, because they are so thin. In many ways they are just form.

And then one day I wrote to her, and that was devastating. It was like someone writing to Henry Moore and him writing back. As it was, we had quite a little correspondence.

What was she saying to you?

She was saying you should apply to the Royal College of Art. Which I did and received a letter asking me to come for an interview. And so I went to London in 1973.

I rang Lucie and there she was; this fabulous lady who only wore white and who came to the door to greet me with her hands covered in white clay. Upstairs it was all Plischke architecture and filled with Hans Coper pots.

Hans was on the interview panel at the Royal College and ended up as my tutor. He was only there one day a week, but he was great. He taught by osmosis. He’d make very minimal comments. I remember he said my work was like walking on a tightrope. That meant a lot to me. He was more a mentor than someone who did practical teaching. What I got from him was the example of a person who was very disciplined, very committed, very focussed. But I never saw him work. He was very ill by that time and very private. But then I don’t like people around like a circus act when I’m working either. Sometimes you have to do the most irrational things and if you have to explain it just gets in the way. And if you are concentrating on something you need to retain the thread of what you are doing.

What did you learn from Lucie Rie?

Single-mindedness. For instance, all her stuff was raw glazed, something that nobody does because you’re glazing things when they are at their most brittle. She took me down to her studio after dinner one night, got this piece out and a big Woolworths paintbrush, slopped the stuff around, started the wheel and there it was. This little frail lady and suddenly you could see the age disappearing because of the deftness of her hands. There is no substitute for experience.

What did you learn at the Royal College?

That I didn’t want to work in an institution and what a fantastic place New Zealand was for getting on and doing things. I learned about industrial techniques. That black could be black and didn’t have to be dark brown. That white could be white and not cream. How to use transfers and decals. I did a lot of experimenting. If you believe, as I do, that my development is about the availability of materials and new things well the Royal College was a major exposure to both. I went to the opera and the National Film Theatre a lot, learnt to eat rice and do all the other things I didn’t do at home.

I was never going to come back. I had work included in a 24 British Potters exhibition travelling to America. Everything was fine—until I went to Greece. I stayed on a remote island for six weeks. I remember thinking, ‘I don’t want to live in a bed-sit all my life’. There’d been a couple of really nasty winters. I wasn’t homesick, but Greece was a big awakening with the sun and the openness of it all. Having come from here you do relate to the landscape and the atmosphere. The space. Greece really made me realise I’d been hoodwinked by the excitement of London. I could have stayed there for the rest of my life. But now I would still be in some grotty bed-sit renting a studio under a railway station somewhere.

What did you do when you got back to New Zealand in 1977?

I was actually offered a job managing the Auckland Studio Potters Centre. I came back and did that for four years. It was the beginning of the Fletcher Brownbuilt exhibitions.

What sort of work did you do when you got back?

Black and white agate. You put black and white clay together without mixing them, throw the piece and then you turn the grey slurry off the surface. It gives a very crisp stratification of clays and colours. Very much a continuation of what I’d been doing at the Royal College.

Did it change when you got back?

No, it evolved but it didn’t change because I was in NZ. My work reacts to where my head is, rather than where my physical body is. I suppose in a sense I was the new kid on the block. An MA in ceramics means nothing to anyone in New Zealand, so people were thinking, ‘What’s he going to do?’ People were interested that I was using an electric kiln.

The use of an electric kiln at that stage was unusual wasn’t it?

There were lots of hobbyists using them but Brian Gartside was the main serious one. Warren Tippet later moved from high-fired work to low-fired work, and started all that brightly decorated peasant stuff. That really put electric kilns on the map.

I was always interested in straight lines and pure white, or pure back. When you’re trying to fire in a fuel kiln that’s warmer on one side, or on the top than on the bottom, that’s flashing bits of stuff onto glazes. All those lovely things that are good about fuel kilns were just irritations to me. The purity of the electric kiln, the fact that you got out exactly what you put it, was what was important. The fact that I had more control over the purity or simplicity of things.

So how did your work change? What was the sequence?

I got into grey because with agate you end up with a whole lot of black and white turnings which, when you reconstitute them, end up being grey. So I had a lot of grey clay lying around! I did grey works with tiny little fissures of black and white in them. I was also doing inlaid lines, just cutting fine lines into the grey, so you had an incredibly fine line. I did pink and blue and yellow.

My next big breakthrough was with brightly-coloured glazes. The first real colour I did was yellow, red and blue in the early 80s. I always kept experimenting. I’ve always been keen on extremes. I’ve never been fond of pastel things. I like blue to be blue, yellow to be yellow, red to be red.

Where do you think this extreme attitude comes from?

I think I’m an all-or-nothing sort of person. I really do like the extremes of yes and no. I’m not very keen on the maybe. It either is or it isn’t.

But now you work almost exclusively in white. What has prompted you to do this white work and to do it for so long?

Hans Coper, my great hero, worked in one clay and one white slip and one glaze all his life. He only used those three variables. Since I’ve been seriously working, I’ve liked the idea of setting up rules. I’ve always loved this kind of mind-game. You can only make cylinders, cones and spheres. The more you limit yourself the more you create possibilities. My shows have always been about very simple ideas and concepts. But I don’t work them out ahead. The exhibition forms as I work. One piece leads to another. I’m interested in my work being seen as a coherent body, as a group. I have been from the first show I had at New Vision in 1973 before I went away. I’d planned it and displayed it and I was in control of the way it looked. In the eighties, Rick [Rudd] lived down the road and we used to talk a lot about our work, and how you could simplify things.

Where do you think this desire to work within the confines of self-imposed rules came from?

Perhaps it was something to do with being an only child. Being my own company and my own friend. Me making up games for myself, to amuse myself. I really love setting up problems for myself and solving them.

You’ve never tried to hide your debt to Lucie Rie. How do you feel about the criticism that your work is still in her thrall?

Without being bizarre and ugly it is quite difficult to make something which is not in some way reminiscent of something else. At the time I was doing the early agate pieces I didn’t notice it. I mean the agate technique is very old, Crown Lynn did it, Luke Adams did it. But I wasn’t glazing and Lucie was glazing and I wasn’t using the impurities through the clay. I was using black and white, something she never did. I don’t think the shapes were hers either. They were shapes I had made before I met her and Hans. They are the shapes I was naturally attracted to. The big idea I did pick up from them was the act of joining things. The fact that you could make a big piece by joining up little bits. It’s the same with Keith Murray. I mean I am terribly influenced by him but I don’t think that I’m copying individual pieces that any of them made. In the end a cylinder is a cylinder. But it’s never worried me at all. I just got on and did it.

Has your theatre work impacted on your ceramics?

Everything does because the common denominator is me. And what’s in my head. But I’m more influenced by things that I find in junk shops, like ceramic insulators, precision marine fittings and things like that. I love the ambiguity of things. Is it a bottle? Is it an insulator?

What else has influenced you?

Design has had the biggest impact. An awareness of Keith Murray, Crown Lynn and how things are put together. But the biggest impact on my work was my confidence to take a stand. I lived on my own and I could make decisions without having to explain to anyone. Now people have started collecting my work and are interested in the direction that I am going rather than my having to make a product for an existing market. That certainly encourages me to push further.

What are your expectations of your work in terms of function?

There’s a wonderful Marguerite Wildenhain quote: ‘All pots are functional including those that are purely decorative because that is their function.’ The function of my work has always been to occupy a space. James Mack used to say about display that ‘Things should be allowed to radiate their own excellence’. I love that.