"a whiter shade of white" article in NZ House and Garden Magazine

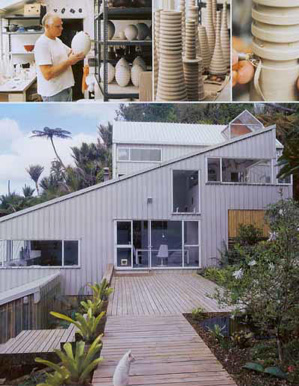

John Parker’s home is as much a work of art as his ceramics

Prue Dashfield has a private viewing

Most of John Parker's ceramic work is as smooth and white as the beaver, cat, possum and coyote skulls in his second bedroom. But the glaze on the angular pieces in his sitting room window has the hokey‑pokey texture of the alligator's skull, though hokey‑pokey was never as white as this.

John Parker, ceramicist and Designer, is the personification of white. Since 1996 he has made his austerely beautiful, grooved ceramic pots only in white because ... well, just because. The interior of his house is almost entirely white as is the terraced garden he has created in dense bush beyond Auckland's Titirangi. Not all of the vegetables are white but only a caterpillar dines exclusively on cauliflowers.

Yet when he mentions his cat Lucie and I ask if Lucie would by any chance be white, he looks at me as if I have the sight and asks ingenuously, "How did you guess?"

His six‑tier house, entirely clad in bone-coloured long‑run roofing iron (it wasn't available in white), is a simply but gracefully and idiosyncratically furnished work of art. Chairman Mao Zedong busts, badges and portraits survey the dining table. The second bedroom's an ossuary of bleached and beautiful bones and the taxidermist's art, the bathroom an irreverent shrine of Catholic iconography. Male dolls stand shoulder to shoulder on the white floor of John's white bedroom, otherwise furnished with just a mattress, lamp, telephone and chandelier.

Heavy greenish industrial glass is displayed on the fridge and on a kitchen ledge a row of ceramic insulators from electric power poles that look for all the world like desirable small works by John Parker.

"I like the ambiguity of things. Is it a bottle? Is it an insulator?" he says in John Parker ‑Ceramics, published to coincide with the exhibition of the same name currently at the City Gallery Wellington ‑ a nineteen metre‑long "still life" of his ceramic works.

He is the only child of an English father and a New Zealand mother who met in Waitara and eloped to Auckland. His dad drove petrol tankers, his mother made electric fence units. Money was tight but there was always enough for books and his parents created their own kinds of beauty.

"My mother's jars of preserves were always beautiful things. My father's art was a well‑trimmed hedge and a well‑trimmed lawn and little gardens of nasturtiums around the fruit trees."

Half John's livelihood is derived from set design for theatre and props from his productions have followed him home. The movie theatre, the only room in the house that isn't white, is painted "John Parker Blue" ‑ a colour specially mixed to match the lapis lazuli artefacts in The BellSouth Pharaohs exhibition John designed for the Auckland Museum in 1997.

Furnished with plush‑covered armchairs wearing lace antimacassars the theatre ambience is so Chinese‑front‑parlour he's tempted to move his Maos up there. He is treasurer of the Auckland branch of the New Zealand China Friendly Society and the likenesses of the late Chairman (John queued to see him lying in state in his crystal coffin) and the Chinese paintings, embroideries, calligraphy and lanterns in the house spring from his interest in the cult of personality (Mao) and a lifelong exposure to Chinese culture in general.

"I grew up in Panmure and all our neighbours were Chinese. They were like my extended family. Mrs. Lum up the road used to play old 78s of Chinese opera and we ran around screaming like cats but even so it must have been something I got used to hearing at a formative age."

He bought his 0.4ha at Oratia in 1969. He couldn't afford land closer to town and wanted to be "a hippie drop‑out" but it was many years before he asked his friend Roger Paul to design the house. John gave him scant instruction because Roger knew his client's likes and dislikes but he wanted a white space in which to exhibit his work and plenty of cupboards to keep it in.

The finished house had many more windows than the one on the drawing board ‑ "We decided where to put them as we built it. We'd say `Hey, the view's so good out there let's have a window'." In winter the house can be cold because there are no curtains to obstruct outlook or light, important in such a rainy neck of the woods and crucial to an artist.

When he told his school careers advisor that he'd like to be either an architect or an interior decorator she replied that there were quite enough architects already, that interior decorating was an unsuitable occupation for men and that the thing for you, my boy, is science. After two miserable years at Auckland University failing chemistry, physics and maths but anxious not to upset his parents, he made a secret application to teacher's training college. He needn't have worried ‑ his parents were delighted. He abandoned science for arts subjects and ate up the course.

His unhappy start in tertiary education had at least introduced him to the sensuousness of pottery at a university club and he subsequently established a correspondence with his future mentor, London based Viennese potter Lucie Rie ‑for whom his cat is named ‑ who recommended the postgraduate Royal College of Art to him. The college refused his application but advised him to go to London anyway and when he presented himself before the interview panel he received a research fellowship that funded his work there for a year; then an honorary BA in ceramics and enrolment in a two year Master's course. This time the fees were significant, the necessary £6000 provided by his ever‑encouraging parents.

In 1983 he plunged into the deep end of a new career in Design ‑ Cabaret. Credits since include Chess, Into the Woods, Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead, Chicago and most recently The Marriage of Figaro and Waiting for Godot. But he considers The BellSouth Pharaohs his most exciting project.

"To hold something that was made in 400OBC was pretty cool. And there were mummified cats and things which I loved . . . "