The Organic Nature of Sophistication

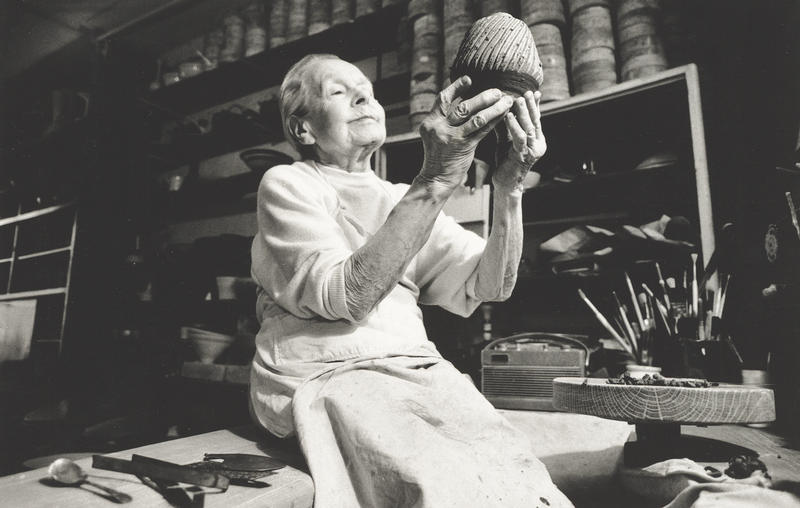

Lucie Rie remembered

"Art is not a profession. There is no essential difference between the artist and the craftsman. The artist is an exalted craftsman. In rare moments of inspiration, moments beyond this life, the grace of heaven may cause their work to blossom into art. But proficiency in a craft is essential to every artist. Therein lies a source of creative imagination."

Walter Gropius :The First Bauhaus Manifesto. 1919

Lucie Rie was the most sensitive, aware, individual and uncompromising potter I have ever known. To say she was been the greatest influence on my own work is the understatement of the century. She was a constant inspiration, working right up into her nineties until she had a stroke about 3 years ago. I was personally devastated when the Off Centre column in Ceramic Review published an attack on her questionable worth as one of the important influences of twentieth century ceramics. It hurt me deeply. I really felt like answering back but couldn't. My 1995 show at MASTERWORKS Gallery opened on the day she died. It was a strangely positive omen that bought a flood of wonderful thoughts along with the tears. I have wanted to write my feelings about her, for a while now but I haven't wanted to be another hanger-on to jump on the eulogy bandwagon. She is too important to me for that.

When I began working with clay and a potter’s wheel in 1966, the New Zealand norm closely followed the Leach/Hamada/Rhodes aesthetic of truth to materials, which manifest itself in the natural beauty of iron bearing clays reduction fired mostly in oil fuel kilns. Electric kilns were regarded as an amateur joke. The results gave the overall brown and green tradition which was all pervasive. In the pottery heydays of the sixties, so much of the work was mock traditional, mock Japanese, clumsy, roughly finished, unevenly glazed with dribbles. All this hid behind the guise of spontaneity. Honesty, humility and expression of the rugged qualities of clay were often a smokescreen for lack of craftsmanship. The random flashing and firing marks amounted to cosmetic surgery. It was never really my thing but I tried to conform and managed to work within the system. Firstly trying to throw white earthenware clay which felt more like a casting slip and then by manipulating a magical ingredient SN1 with Crum Clay, I managed to get a relatively iron free clay to experiment with white glazes on. Trevor Bayliss mixed the first porcelain clay from refined ingredients, but David Leach Porcelain was yet to come as a product of the late 70’s. As beautiful as the traditional Chinese and Japanese objects were and still are, I felt out of place with the oriental mentors.

Then one day in 1967 Tony Birk’s THE ART OF THE MODERN POTTER was published and I discovered Lucie Rie and Hans Coper and the Bauhaus and a European aesthetic which joyously celebrated the machine and technology and precision. Form followed function rather than emulating nature. It changed my life. I had a real mentor at last and one that was well respected and still used an electric kiln. One day with all the naiveté and arrogance of a 21 year oId I actually wrote to Lucie and asked if I could come and work with her. She suggested instead that I should apply for the Royal College of Art. Years and many letters later I did go there. Hans Coper was my tutor and I graduated with an MA Degree in Ceramics in 1975. I am certain Lucie had a lot to do with the whole process of me getting in with an honorary BA Degree, although she would never take any credit. She found me a place to live with young friends of hers and would periodically have me over for dinner because she thought I wasn’t eating properly. She always cooked sensible things because she said “ New Zealanders liked sensible things.” She introduced me to her great friend Ian Godfrey, and we shared a workshop for a year before I returned home.

I have many great memories; like the very first meeting when she came to the door dressed in white, with a white apron and white porcelain clay on her hands; the legendary poppy seed cake; The Joseph Hoffmann glasses; the talk of an aristocratic childhood in Vienna and holding her feet as she dived into her large electric kiln to lift out the heavy shelves. Always there was a generosity of spirit. After I returned home she always made time to see visiting friends I passed her phone number on to. The last time I saw her was in 1988 on the ill-fated Faenza reconnaissance trip.

Lucie Rie epitomises all that I find desirable in pottery. Her work is highly sophisticated but the apparent simplicity is highly deceptive. I believe the more her work is refined, the more she is concerned with simple variations of basic ideas, then the more the essential qualities of clay are being expressed. In the Hand Crafted Ideal this is as much an apparent contradiction as labelling her work “Potter’s Pots”, but they are. They contain so much information about clay, glazes, the throwing process and the effects of temperature, but they are like people who silently know more than they are letting on. The implications one may deduce from supposedly simple or straightforward effects are staggering. All you need to do is work out how to decipher them.

In the introduction to the catalogue for the 1967 Arts Council retrospective exhibition of her work George Wingfield Digby wrote “Here was a studio potter who was not rustic but Metropolitan. Her work had the nostalgic undertone of Folk Art.” She always worked within the area of traditional studio pottery, because all her ware is recognisable as buttons, bowls, bottles, cups, jugs, vases etc. Although some of her inspiration comes form early Roman pottery found in Britain, her work is contemporary and sophisticated. This is not surprising since Greek and Roman pottery was all about control and precision : the potter’s skill of throwing and turning vs. the kiln’s random enhancement. She never needed to resort to using the bizarre for effect. She was concerned with essence : The paring away of unnecessary features like stuck on appendages or ruinous brush painting. Lucie decorated and complicated her work with restraint and from a limited vocabulary of methods and simple variations. Her favourite forms recurred with subtle changes in size and proportion rather like the a group of plants of the same species - the are all theoretically the same, with a shared common origin but none are exactly identical.

Her forms are stark, often severe, but are far more related to the forms and principles and refinement of natural things than the pseudo natural sculptural ceramic artworks which proffer to know what it is all about, but which end up as parodies of the nature they are trying to homage, rather than expressing any of the abstract subtlety of evolution, development and slow considered change.

There is no obvious clay quality about her pots, but the more turned and distinctly shaped, with all the variables held in a certain degree of control, the more one may deduce about the properties of clay. Certainly it would not be possible to make her work in any other material.

The whole process of throwing says so much about clay. How it has plasticity and can be stretched and formed and while on the wheel it is a very organic material which is flexible and sensitive to the slightest of pressures by the hands and fingers. All this is present in her work without the superficial clues of throwing ridges to indicate they are hand thrown objects.

Her forms show how clay can be manipulated. She often pushes a piece oval or cuts major furrows or fine fluting. Pieces are often made in sections and joined while still wet. The subsequent finishing obliterating the obvious joins with the piece drying as a whole.

All her work was raw glazed and subsequently fired in an electric kiln to 1250 º C. By its very nature the raw glazing process is difficult, since unfired green ware is pottery in its most vulnerable state, brittle to the touch and still sensitive to water breakdown. Add ware which is very finely turned and it is a prescription for disaster. She showed me one evening, the technique of applying thick slurry glaze as the bone dry bowl spun on the wheel head. Not a hand-tied bamboo and dog hair brush in sight, she always used clumsy Woolworth’s house painting ones because they gave a better coverage. She added Gum Arabic, ”Not too much and not too little” to make the glaze stick. The piece was then painstakingly dried back to bone dry again and the process repeated inside and thoroughly dried again before a slow single firing. The pitfalls of raw glazing end up being its virtues. Because the clay is still receptive to water, the glaze actually penetrates into the clay and the two contact layers mix a certain amount and the clay and glaze have a relationship which is intermeshed rather than just being a surface coating on bisque ware. Bloating is an ever present problem however. With raw ware you have to lift a bowl carefully with both hands, you can’t pick it up with two fingers on the rim. A potter has a much more intimate relationship with the pieces themselves because so much extra care is needed in handling and timing the drying. I feel that this quality of gentleness in handling, care and intimacy can be sensed in the final pieces. To dismiss this attribute as a mere feminine element is to miss the point. This is an artist who is an expert craftsman, who fully understands the process and its limitations and who can work within and boldly exploit these limitations with a knowledge that only comes with time and experience.

No-one made thrown and turned porcelain that is as thin or as delicate. However the pieces never have a mechanical or a lathe-turned or a machined static rigidity. The flared rims of the bottles undulate and sometimes distort in the firing under the gentle tension of gravity. No matter how crisp and sharp your throwing and turning may be, the high firing process and the clay/glaze meshing means that the clay is on the verge of melting and warping and distortions occur, but these are the same distortions as leaves sagging under the weight of water droplets or flowers being blown out of shape by a gentle wind. There is a softening and an organic quality which is being caught in a moment in time and held. It also records the way in which clay unwinds in firing in the opposite direction to the wheel spin, or the flow path of a particular glaze material.

Lucie often coloured or textured her oxidised clay with additives. With the clay and glaze interacting so closely, these affected the resulting glaze surfaces, sometimes causing them to pit or bubble. A particular clay from Chesterfield mixed with “T” Material caused a decorative crawling. Other glazes used silicon carbide for a volcanic pitting, which also gave the added bonus of local reduction copper pinks in the otherwise oxidising atmosphere of her electric kiln.

Lucie used many clays and glazes and chose each carefully to compliment the other. Sometimes flecks of colour break through or metallic particles melt in characteristic flow paths. Because the colouring oxides were often in the clay rather than the glaze, there are subtle depths of colours, blues, greens, browns and greys which have their origin somewhere in the distance within the clay at some intangible secret place as if the colour is slowly seeping from an internal source. One has the feeling that these pieces are dynamic, moving and breathing rather than suffocated and embalmed under an impervious sheet of plastic glaze.

The agate pieces involved the use of two different clays within one piece but without mixing them properly together, so that the action of throwing causes spirals of differing colours and possibly textures. This spirally is a unique property of throwing. When the pieces are glazed, the additives react to the glaze in their unique ways. So it is possible to have one glaze that is both smooth and pitted on the one piece where it crosses different clay strata.

A characteristic of her work has always been the use of sgraffito. Often she applied her beloved Manganese Dioxide or the Manganese/Copper “Bronze” mixture, brushed onto the bone dry raw clay, with only water and a little Gum Arabic. She then scratched the fine sgraffito lines through the oxide coating into the clay with a pin. The effect is very precise and machine like at a distance, but close-up the lines have a slightly feathered edge from the dry clay splintering under the pressure of the pin. The same quality does not happen in metal, wood or glass. The complete reverse of sgraffito is inlay. Lines or furrows are scratched into raw clay and filled with a coloured clay or slip and turned back to reveal precise lines in the normal body. In this way the inside of a bowl may be treated as a negative of the outside with respect to glaze treatment.

Her special magic is her attention to detail. All her pots have turned feet even those which are not obviously visible. They were glazed with only the foot ring cleaned for stacking in the kiln. Some rare bowls had an unglazed ring inside so that another bowl could be economically stacked inside, as some ancient Chinese ware was fired. Often the insides of feet have a delicate sgraffito pattern that is an unexpected surprise to discover when inverting while handling.

The wholeness of each piece is a quality found in nature, but her forms never mimic nature. They never look like something else. They are concerned with the same ideas as natural shells and stones. i.e. If you turn them over there is not an ugly part that you are not meant to see. The pots can be viewed from all angles There is not a single way of looking. They were not made to specifically stand or be displayed in one particular way, just as trees and flowers do not have a front and a back. There is no large unglazed area of clay which says “I am the bottom of this pot and I should be sitting down on something and never be picked up ”. Even if her pieces are never picked up and examined all over, the point is that she has bothered, taking that extra amount of care about the finish outside what is just necessary.

To the end she was continually developing new glazes. Every firing had a new glaze test. Parts of her hand written glaze sketch/note books have recently been published. They are such a personal working diary, it is somehow fitting they appear as some indecipherable hieroglyphic archaeological find. Hans Coper wisely destroyed all his notes before his death. Hans began as her student making ceramic buttons, during the war, in the tiny workshop at 18 Albion Mews. Lucie always regarded him as her greater teacher.

She certainly was mine.